Published February 2006 in

Zeek: A Journal of Jewish Thought & Culture

http://www.zeek.net/christianzionism/

The 2004 U.S. presidential elections left little doubt about the rise of the Christian Right. Polls indicated that “moral values” topped the list of voter concerns, surpassing the economy, the environment, and even the war, and the symbolic campaigns against gay marriage and abortion mobilized broad sections of the electorate, in particular the "five million new Evangelical voters" whom Karl Rove promised, and delivered, to his president. A year and a half on, the rise of the Christian Right is keenly felt in many areas. Soon-to-be Justice Samuel Alito is certain to enshrine its moral agenda within the Supreme Court's new "strict constructionist" jurisprudence, which allows government much more latitude in regulating moral conduct, even as its "new federalist" doctrines constrict the government's regulation of economic conduct. The "mood" of the country is said to be drifting rightward. And, of course, Israel. As Israel enters its own election season (and the Palestinians conclude theirs, with ominous and uncertain results), the role of the deeply influential phenomenon known as Christian Zionism is increasingly becoming better known. On the surface, Christian Zionism seems benign enough. It appears to be steeped in concern for the fate of the Jewish people and grounded in sympathy for the Jews’ long history of persecution and yearning for a homeland. Christian Zionist leaders often claim deep admiration for the Jews, describing them as “God’s Chosen people.” However, beyond the outpouring of support for Zionism and Israel that has long been part of the conservative Christian movement lies an apocalyptic motive that is troubling, even sinister, in its implications for both the Jewish people and the global community.

It is well known that Christian Zionism derives its ideology from the belief that the Jews have a role to play in the End of Days: the Jews' dominion over Israel is, itself, a sign of the impending apocalypse, and the presence of the Jews there is essential for the predicted apocalyptic drama to unfold. Less well known, however, are the details and history of that doctrine, and exactly how seriously it is taken today. In fact, predictions of apocalypse are taken very seriously. According to a 1999 Newsweek poll, 40% of Americans (45% of Christian Americans; and 71% of Evangelical Protestants) believe the world will end as the Bible predicts. And of that population, 47% believe the Antichrist is already on Earth, now. In other words, the apocalypse is not an abstract, far-off notion. Thus it is urgent to inquire after its history, and consider its consequences today.

A Brief History of the End of the World

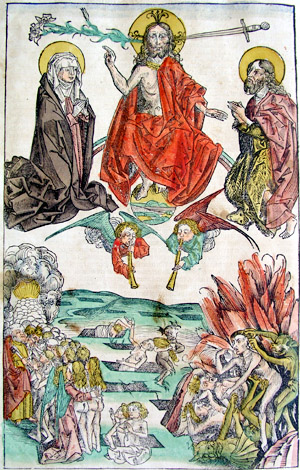

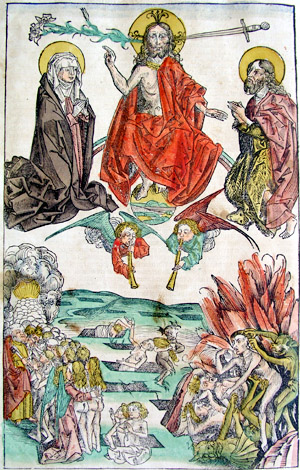

Although Christian Zionist ideology draws from the Old Testament books of Daniel and Ezekiel, its primary inspiration is the New Testament's Book of Revelations. Revelations details a horrific vision in which Earth is largely decimated by a series of plagues, and an “animal with ten horns and seven heads” emerges to lead the peoples of the world into blasphemy and destruction with the help of another beast performing false miracles and bearing the mark (666 -- originally a numerological reference to the Roman Emperor Nero, but now, of course, bearing other connotations). Following the appearance of a Lamb, generally thought to symbolize Christ, a great battle ensues between the forces of good and evil. All of humanity is divided into the categories of “saved” and “unsaved,” the former of which are destined to be “raptured up” to God while the rest of humanity perishes in a gruesome scene of global carnage.

Although Christian Zionist ideology draws from the Old Testament books of Daniel and Ezekiel, its primary inspiration is the New Testament's Book of Revelations. Revelations details a horrific vision in which Earth is largely decimated by a series of plagues, and an “animal with ten horns and seven heads” emerges to lead the peoples of the world into blasphemy and destruction with the help of another beast performing false miracles and bearing the mark (666 -- originally a numerological reference to the Roman Emperor Nero, but now, of course, bearing other connotations). Following the appearance of a Lamb, generally thought to symbolize Christ, a great battle ensues between the forces of good and evil. All of humanity is divided into the categories of “saved” and “unsaved,” the former of which are destined to be “raptured up” to God while the rest of humanity perishes in a gruesome scene of global carnage.

Although most Christians interpret Revelations as allegory, Evangelical Christian Zionists tend to adopt a literal approach. Of course, "literal" is itself not entirely literal, since chariots and fire are not exactly airplanes and missiles. However, when questioned about the discrepancy between John’s descriptions and the realities of modern life and weaponry, they assert that John was merely relaying what he saw through the only language he knew. Thus, helicopter gunships become “locusts” whose wings sound “like the noise of a great number of chariots and horses rushing into battle” (9:3-10), and nuclear missiles become “a great star [that] fell from heaven, blazing like a torch” (8:10). Indeed, it is thought that recent advances in technology account for much of the growing belief in apocalyptic prophecy, particularly as the world entered the nuclear age.

In America, Christian Zionist doctrines have their roots in 17th century New England, where millennialism (the anticipation of the Second Coming, preceded by a period of global turmoil) emerged among the Puritans. The Puritans, who viewed themselves as the new Israel, expressed interest in Jewish conversion and restoration of the non-converted Jews to Palestine. Increase Mather, and his son Cotton Mather, often couched his calls for absolute moral purity in proclamations about the impending Second Coming, which required the restoration of the Jews. While the movement was more fervent in England during the 19th century, the Americans began to match England’s fervor with the rise of dispensationalism, pioneered by defrocked Anglican priest John Nelson Darby. Unlike the millenialists before them, followers of dispensationalism maintained that the End Times had already begun. In Darby’s view, world history could be divided into seven distinct epochs, or dispensations, and humanity is rapidly approaching the dawn of the final age. (Mormons, Millerites, and many other sects had similar views.)

Toward the end of the 19th century, Darby collaborated with leading evangelist Dwight L. Moody to establish the Chicago Bible House, which transformed the premillenialist movement and became one of its major training centers. Moody’s sermons were filled with references to Jews, whom he regarded as the sinning sons of Israel who had disobeyed God, as well as the vicious crowd that had called for the execution of Jesus and cried out “his blood is upon us and upon our children.” His sermons contained an unmistakable element of antisemitism, and he also regarded the Jews collectively as a “greedy and materialistic” people, citing the Rothschilds as an example.

This period was also marked by the cultivation of Messianic Judaism, which Moody discovered to be a highly effective missionary strategy, enabling its converts to retain their ethnic identity as Jews while adopting Christian beliefs. Simultaneously, massively popular gatherings such as the Niagra Conferences and the International Prophetic Conferences aided the movement’s development. During one Chicago conference, speaker Nathaniel West reinforced his belief in Zionism by likening the suffering of the Jewish people to that of Christ himself. What many in the Jewish community apparently failed to grasp was that while the sentiment outwardly served as a moving display of sympathy toward the Jewish plight, by Jewish suffering to that of a man who was said to have died for the sake of Christian redemption, West also reinforced the symbolic role of the Jew as scapegoat.

Missionary activity among the Jews grew following the establishment of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. The institution’s ambivalent attitude toward Jews was embodied by one of its early directors, James M. Gray, who outspokenly denounced anti-Jewish violence on the one hand, while on the other expressing the belief that the infamous Russian forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was authentic evidence of a global Jewish conspiracy. In 1891, Moody disciple William E. Blackstone bridged the gap between Christian Zionist belief and political activism by launching a petition endorsing Jewish restoration in Palestine. The petition, signed by 413 eminent American leaders, helped deepen ties between Blackstone and Jewish community leaders, leading to the formation of the Christian-Jewish Conference of 1890. Because of Blackstone’s support of Zionism and efforts on behalf of the persecuted Jewish community in Russia, he established lasting contacts with leaders of the American Zionist movement, such as Adam Rosenberg, president of the New York branch of Hoveve Zion (Lovers of Zion). Though Blackstone had, in his influential book Jesus Is Coming, attributed Jewish suffering to the Jews’ failure to accept Christ, he appeared frequently as an honored guest at Zionist conferences and had close relationships with Zionist figures such as Nathan Straus and Stephen Wise.

Missionary activity among the Jews grew following the establishment of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. The institution’s ambivalent attitude toward Jews was embodied by one of its early directors, James M. Gray, who outspokenly denounced anti-Jewish violence on the one hand, while on the other expressing the belief that the infamous Russian forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was authentic evidence of a global Jewish conspiracy. In 1891, Moody disciple William E. Blackstone bridged the gap between Christian Zionist belief and political activism by launching a petition endorsing Jewish restoration in Palestine. The petition, signed by 413 eminent American leaders, helped deepen ties between Blackstone and Jewish community leaders, leading to the formation of the Christian-Jewish Conference of 1890. Because of Blackstone’s support of Zionism and efforts on behalf of the persecuted Jewish community in Russia, he established lasting contacts with leaders of the American Zionist movement, such as Adam Rosenberg, president of the New York branch of Hoveve Zion (Lovers of Zion). Though Blackstone had, in his influential book Jesus Is Coming, attributed Jewish suffering to the Jews’ failure to accept Christ, he appeared frequently as an honored guest at Zionist conferences and had close relationships with Zionist figures such as Nathan Straus and Stephen Wise.

Later, in 1909, Cyrus Scofield published the Scofield Reference Bible, which became the Bible of the fundamentalist movement and the central text to which Christian Zionists have since referred. Scofield’s crystallization of what has been called “End Times Prophesy” emphasized the necessity of a Jewish return to the Holy Land (especially Jerusalem), the destruction of Islamic holy sites on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif), the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, the imminent battle of Armageddon, and the mass conversion of the surviving Jews to the Christian faith.

====

Contemporary Fervor and Republican Politics

The 1967 war and the Cold War created a climate in which Christian fundamentalists were particularly receptive to Scofield’s views on Revelations. In the 1970s, his “End Times Prophecy” found an enormous audience thanks to author Hal Lindsey, whose 1970 The Late Great Planet Earth was a New York Times bestseller that sold over 18 million copies in English and 20 million copies in 54 other languages. Lindsey views are clear. “The valley from Galilee to Eilat,” he once declared, “will flow with blood and 144,000 Jews will bow down before Jesus and be saved!” The rest of the Jews, according to Lindsey, are destined to perish in “the mother of all Holocausts.”

Lindsey’s novel has sold well throughout the last three decades and even enjoyed a spike in sales in August and September of 1990, as fears peaked over Iraq’s Hussein regime and, according to a CNN poll taken at the beginning of the Gulf War, 14% of Americans believed they were witnessing the beginning of Armageddon. Lindsey’s success also signified the creation of a popular genre, including the influential work of Timothy LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, co-authors of the Left Behind series, in which Christian protagonists assassinate a former U.N. head who is revealed to be the Antichrist. The series has sold over 50 million copies.

The 1980s saw the election of Ronald Reagan, who had espoused Christian Zionist views in the past, and who enjoyed a close friendship with the evangelist Rev. Billy Graham. According to Reagan’s former legal secretary Herb Ellingwood, Reagan had developed a nearly obsessive fascination with apocalyptic prophecy, reading scores of apocalyptic novels. As governor, and later as president, Reagan became known for quoting Ezekiel, confiding to State Senate leader James Mills at one point that “everything is falling into place. It can’t be too long now. Ezekiel says that fire and brimstone will be rained down upon the enemies of God’s people. That must mean that they’ll be destroyed by nuclear weapons. They exist now, and they never did in the past.”

By the time of George W. Bush’s induction into the White House, approximately 40 million Americans expressed beliefs that fall within the scope of Christian fundamentalism, and that number increased dramatically following the attacks of September 11, 2001. Like Reagan, who often framed the struggle with Communism in language rife with religious overtones, George W. Bush has framed the War on Terror in a like manner, presenting the conflict in apocalyptic terms as “a monumental struggle between good and evil, [in which] good will prevail.” Along with frequent references to “evil” and “evildoers,” the President remarked in his September 20, 2001 speech before a Joint Session of Congress that “God is not neutral” in the War on Terror. Similar imagery has been echoed by evangelical leaders such as Falwell, who in 2002 infamously referred to the prophet Muhammad as a “terrorist” in a 60 Minutes appearance.

Evangelical Christianity and a steadfast belief in Biblical prophecy have been a driving force throughout the political career of George W. Bush himself, who in his late 30s became a born-again Christian and was formally converted by Rev. Billy Graham. Before announcing his candidacy, Bush met with Texas evangelist James Robison, confiding that he had given his life to Christ and felt that God wanted him to be President. According to Stephen Mansfield, author of The Faith of George W. Bush, he further revealed that he felt “something was going to happen” and the country would need his leadership during a time of crisis. Since assuming office, the President has been openly forthcoming with his religious convictions and the central role they occupy in his foreign policy decisions. According to veteran journalist Bob Woodward, Bush once declared that he would “export death and violence to the four corners of the earth in defense of this great country and rid the world of evil,” and he also allegedly told Palestinian Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas that “God told me to strike al-Qaeda and I struck them, and then He instructed me to strike at Saddam, which I did.”

Christian Zionist ideology also remains a factor in the growing inclination toward American unilateralism. Among evangelicals, mistrust of the United Nations is often reinforced by religious leaders such as Pat Robertson, who wrote in his book The New World Order that the UN and the Council of Foreign Relations may be part of a “tightly knit cabal whose goal is nothing less than a new order for the human race under Lucifer and his followers.” The connection between unilateralism and evangelicalism, also a prominent feature of the Christian Right during the Cold War, stems from references in the Book of Revelations to a one-world governmental body (symbolized by a many-headed dragon) led by the Antichrist. In the face of a conflict of interests between Christian fundamentalists and the U.N. or E.U., the latter organizations have sometimes become the biblical “many-headed dragon” haunting the imagination of the Christian Right. The theme of the U.N. or E.U. as an implement of the Antichrist has been reinforced in apocalyptic literature from Lindsey to Robertson, highlighting a climate of American unilateralism and mistrust.

The Fine Line Between Philo- and Anti-Semitism

One of the particularly troubling aspects of Christian Zionism is the existence of explicit antisemitism within the movement. While most Christian Zionists are not overtly antisemitic, and while many feel genuine sympathy toward the Jewish people, there exists an undeniable undercurrent of anti-Jewish sentiment within the Christian Right. At its core level, the Christian Zionist ideology has Jews play a sacrificial role in the redemption of the Christian world, whether they like it or not. Additionally, some of the movement’s most influential leaders have issued remarks that reveal a far less friendly picture of evangelical Christian attitudes toward the Jewish people on whose behalf they claim to fight.

The most recurrent anti-Jewish sentiments among members of the Christian Zionist movement reflect deeply rooted Christian stereotypes that date back centuries, pertaining to the refusal of Jews to accept Christ, myths of Jewish greediness and money-savvy, and fears of Jewish conspiracies toward world domination. In fundamentalist Christian sermons, Jews are often referred to as “spiritually deaf” or “spiritually blind,” and their status among the “unsaved” is an integral part of evangelistic belief. Rev. Dan C. Fore, former head of the Moral Majority in New York, once professed, “I love the Jewish people deeply. God has given them talents He has not given others. They are His chosen people. Jews have a God-given ability to make money. They control the media; they control this city.” The sentiment has been echoed by Falwell, who remarked during one sermon that “a few of you don’t like the Jews, and I know why. They can make more money accidentally than you can on purpose.” Others, such as Rev. Donald Wildman, founder of the American Family Association, have adopted the view of evangelical leader R.J. Rushdoony’s conviction that the mainstream television networks promote anti-Christian values because they are mostly controlled by Jews.

At the same time as these dark undertones exist beneath the surface, Christian Zionists are -- on that surface -- very generous in their temporal (and perhaps temporary) support of Israel. They support the Nefesh b'Nefesh program, which subsidizes the costs of immigration to Israel. They support Israel in its struggles with the Palestinians and others. And they are increasingly coming to Israel, in greater and greater numbers. The Likud candidate for Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has made a point of cultivating support among Christian Zionists, both to help him politically and to invest in Israel; he recently disclosed conversations to build a network of large, high-end hotels for Evangelical visitors, and a DVD interview with him is being sold on Hal Lindsey's website, which, like most Christian Zionist sites, assumes a pro-Israeli-Right political stance. Other Israeli politicians, and leaders of the Jewish Agency, are aware of the ulterior motives the Christian Zionists have for bringing Jews to Israel, but then again, since Jews don't believe in the prophecies anyway, they seem to feel that they have nothing to lose. Let the Evangelicals be disappointed when the Rapture doesn't happen; in the meantime, they are steadfast political and financial supporters of Israel. Whether this turns out to be a marriage of convenience or a "pact with the devil," of course, remains to be seen.

On the American side, the instrumental role formed by the Christian Right in U.S. foreign policy is rarely treated with the level of acknowledgment and importance it clearly warrants. In fact, the Christian Zionist movement has had a formidable impact upon American involvement in the Middle East. Christian Zionism, which is woven deeply into the fabric of American religious and political life, constitutes a rapidly growing movement that is certain to continue to exercise the considerable influence it exerts today. The movement’s ideology contains profound implications, and they must be examined closely, for the future of Christian Zionism may have profound consequences for the future of the world.

Published in Volume 63, Issue 24 of the Arizona Jewish Post, December 21, 2007.

Published in Volume 63, Issue 24 of the Arizona Jewish Post, December 21, 2007.

Although Christian Zionist ideology draws from the Old Testament books of Daniel and Ezekiel, its primary inspiration is the New Testament's Book of Revelations. Revelations details a horrific vision in which Earth is largely decimated by a series of plagues, and an “animal with ten horns and seven heads” emerges to lead the peoples of the world into blasphemy and destruction with the help of another beast performing false miracles and bearing the mark (666 -- originally a numerological reference to the Roman Emperor Nero, but now, of course, bearing other connotations). Following the appearance of a Lamb, generally thought to symbolize Christ, a great battle ensues between the forces of good and evil. All of humanity is divided into the categories of “saved” and “unsaved,” the former of which are destined to be “raptured up” to God while the rest of humanity perishes in a gruesome scene of global carnage.

Although Christian Zionist ideology draws from the Old Testament books of Daniel and Ezekiel, its primary inspiration is the New Testament's Book of Revelations. Revelations details a horrific vision in which Earth is largely decimated by a series of plagues, and an “animal with ten horns and seven heads” emerges to lead the peoples of the world into blasphemy and destruction with the help of another beast performing false miracles and bearing the mark (666 -- originally a numerological reference to the Roman Emperor Nero, but now, of course, bearing other connotations). Following the appearance of a Lamb, generally thought to symbolize Christ, a great battle ensues between the forces of good and evil. All of humanity is divided into the categories of “saved” and “unsaved,” the former of which are destined to be “raptured up” to God while the rest of humanity perishes in a gruesome scene of global carnage.  Missionary activity among the Jews grew following the establishment of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. The institution’s ambivalent attitude toward Jews was embodied by one of its early directors, James M. Gray, who outspokenly denounced anti-Jewish violence on the one hand, while on the other expressing the belief that the infamous Russian forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was authentic evidence of a global Jewish conspiracy. In 1891, Moody disciple William E. Blackstone bridged the gap between Christian Zionist belief and political activism by launching a petition endorsing Jewish restoration in Palestine. The petition, signed by 413 eminent American leaders, helped deepen ties between Blackstone and Jewish community leaders, leading to the formation of the Christian-Jewish Conference of 1890. Because of Blackstone’s support of Zionism and efforts on behalf of the persecuted Jewish community in Russia, he established lasting contacts with leaders of the American Zionist movement, such as Adam Rosenberg, president of the New York branch of Hoveve Zion (Lovers of Zion). Though Blackstone had, in his influential book Jesus Is Coming, attributed Jewish suffering to the Jews’ failure to accept Christ, he appeared frequently as an honored guest at Zionist conferences and had close relationships with Zionist figures such as Nathan Straus and Stephen Wise.

Missionary activity among the Jews grew following the establishment of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. The institution’s ambivalent attitude toward Jews was embodied by one of its early directors, James M. Gray, who outspokenly denounced anti-Jewish violence on the one hand, while on the other expressing the belief that the infamous Russian forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was authentic evidence of a global Jewish conspiracy. In 1891, Moody disciple William E. Blackstone bridged the gap between Christian Zionist belief and political activism by launching a petition endorsing Jewish restoration in Palestine. The petition, signed by 413 eminent American leaders, helped deepen ties between Blackstone and Jewish community leaders, leading to the formation of the Christian-Jewish Conference of 1890. Because of Blackstone’s support of Zionism and efforts on behalf of the persecuted Jewish community in Russia, he established lasting contacts with leaders of the American Zionist movement, such as Adam Rosenberg, president of the New York branch of Hoveve Zion (Lovers of Zion). Though Blackstone had, in his influential book Jesus Is Coming, attributed Jewish suffering to the Jews’ failure to accept Christ, he appeared frequently as an honored guest at Zionist conferences and had close relationships with Zionist figures such as Nathan Straus and Stephen Wise.